Kasane

ButtonUrushi lacquer applied in a unique color gradation to twelve masterfully turned zelkova wooden plates. Over twenty alternating processes of urushi application, drying, refining and polishing, resulting in both opaque and translucent pieces, with both high gloss and matte finishes.

Yohko Toda

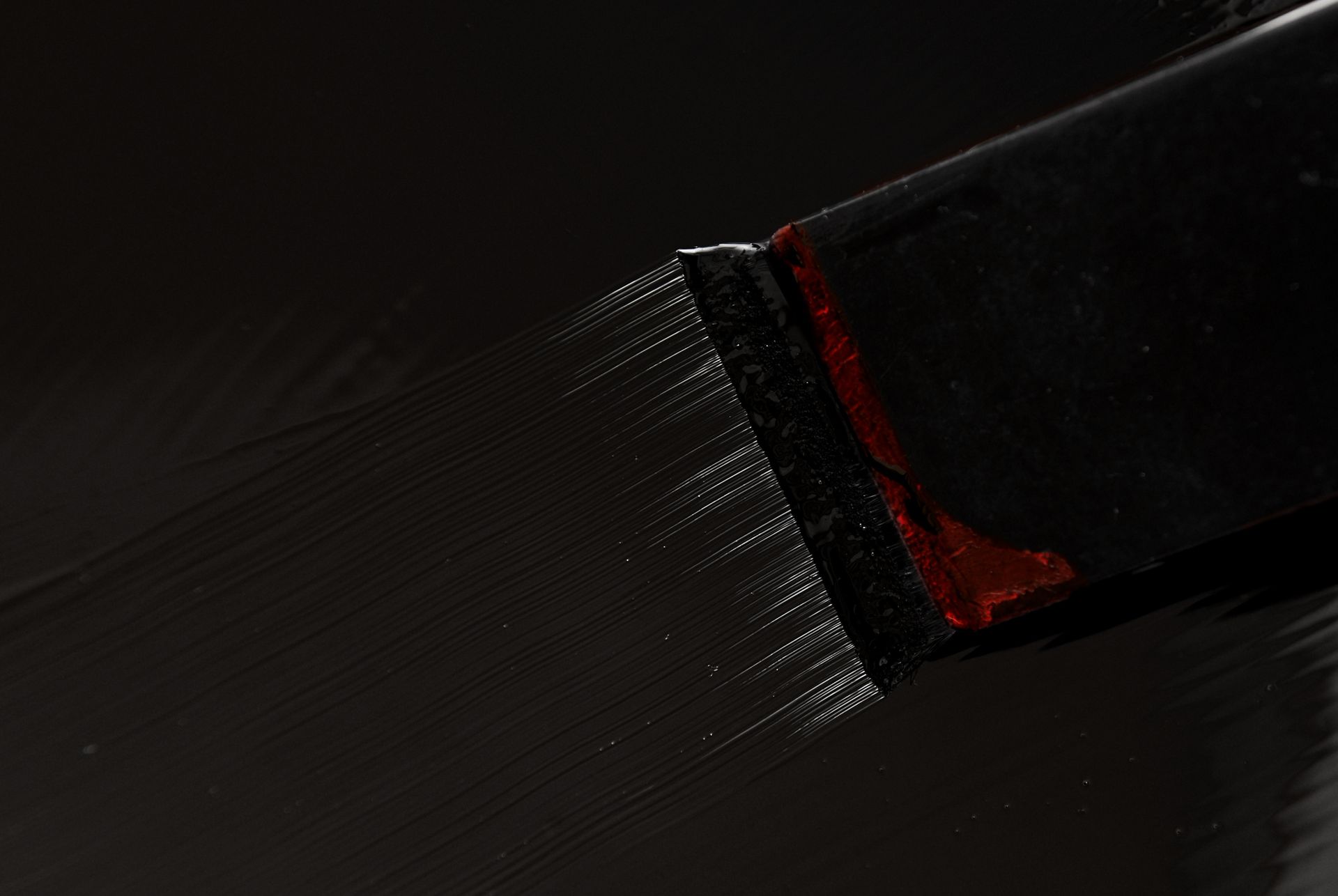

I consider the almost divine beauty and purity of Urushi is at its acme at the instant the liquid is brushed on.

Imagine the moment the tip of the human haired brush puts down Urushi as if it were a thousand strands of flowing glistening black hair.

Imagine the very moment Urushi transforms an object into an unfathomable, visceral, giddying black.

Though freshly dried Urushi shines with the lucidness of a newborn, the excitement gradually subsides and silence follows. Once it drys, the vividness is no longer.

From there Urushi gradually hardens over a 6-month period. In a somewhat lonesome sentiment, the Urushi comes of age I guess. From this point of view, liquid Urushi possesses red hot lava-like chaotic energy and vigor.

The beauty and spiritualism Urushi with which it has enamored people from the ancient times has many faces. When facing Urushi, my body rejoices in a storm of excitement. Sometimes my heart aches, other times experience ecstasy. Sometimes dumbfounded, nearly fainting, and crying without knowing.

Thus I found my vocation to pass along the fascination of live Urushi through multiple dimensions and perspective. 3D, 2D, space, time, concept, etc.

*Urushi-media

Urushi is Japanese lacquer from Urushi tree.

The origin of the word "media" is "medium" in Latin, and means "between," "interposition," and “mediator."

the edit -Yuki Kajikawa

the edit is a brand by Yuki Kajikawa, curator at the Kahitsukan, Kyoto Museum of Contemporary Art.

Throughout my career, I have fostered many connections with artists whose ideas and materials have provided me with a wealth of inspiration. the edit was conceived as a brand of products with stories based on these meaningful encounters.

The concept stems from the myth of the red thread;

a bond between people destined to be soulmates, regardless of place, time, or circumstance, that stretches or tangles but never breaks.

Life is full of unexpected coincidences. Inspired by the red thread, I hope this series of carefully edited items will add color to your life.

Yohko TODA + the edit

Urushi Lacquer・ Kyoto

-

Artist's Story

In order to break with existing notions of urushi lacquer and expand its image as something familiar in everyday life, lacquer artist/artisan Yohko Toda and museum curator Yuki Kajikawa have created a small space where visitors can experience black urushi lacquer with their entire body and all their senses.

-

About the Craft

Urushi 漆, a completely natural lacquer coating, has been in use in Japan for 9,000 years. It is the world’s hardest and most durable coating, and can be applied to wood, metal, bamboo, glass, even over hemp cloth (known as “dry lacquer”). Not only it is a protective coating but it has anti-bacterial properties, is easy to clean, and increases the longevity of whatever it is applied to. Clear urushi coating on wood appears more lustrous and beautiful over time, and the wood grain becomes more prominent.

The clear, honey-colored sap from the lacquer tree (Rhus vernacifera) is collected by hand from incisions on the tree trunk; total output of the precious substance which can ever be extracted from one tree is only six ounces (177 cc). Mineral pigments can be added to create any color, such as iron oxide for black urushi or red iron oxide for red urushi.

During the Heian period (792 - 1185), lacquer-coated wooden functional ware was very popular and Japan became Asia’s undisputed lacquer master during the Golden Age of lacquerware which followed. The Portuguese introduced it to the west in the 16th century and it was widely spread in the 17th century by the Dutch East India Company, enthralling royalty and nobility alike. Marie Antoinette amassed a famous collection of lacquerware items. Japanese urushi ware dazzled the west as Japanism spread during the Belle Époque.

Mother-of-pearl inlay is a process of embedding pieces taken from the iridescent inner layer of mollusk shells (abalone or oyster shell, etc.) into urushi. The pieces of shell are arranged in decorative motifs and most often cover a wooden base. The Japanese adopted this methodology from the Chinese in about the 7th century CE.

Maki-e, the most famous urushi decorative technique, is a 1200-year old, native Japanese process involving the sprinkling of gold or silver power on a decorative design of still wet urushi. Makie motifs can either be in burnished, flat or 3-dimentional raised form.

Hyomon is the embedding of metal sheet as an inlay on an urushi surface

Chinkin is the application of gold into decorative patterns which are incised into the surfaces of urushi vessels.

Kinma involves incising decorative motifs in an urushi surface and filling it with colored urushi. It is believed to have originated in Southeast Asia.

Choshitsu is carved lacquer achieved by applying many layers of colored lacquer, usually to a wooden surfaces, then using a metal carving knife to engrave 3-dimensional designs. It takes at least 100 layers of urushi to achieve 3mm for carving. The technique most probably came from China about 800 years or more ago.

-

Kasane

ButtonThis piece consisting of 12 plates is made only with traditionally available methods and hues. As in the title, the stacked plates compose a color gradation.

In Japan, we are surrounded by the constantly changing seasons. Even during the day, nature’s expression beginning from dawn, daybreak, sunset, twilight… is rich and diverse. I have long loved color and been especially interested in mid-tone hues. Nara, where I grew up and at the foot of Higashiyama in Kyoto where I live, is a melting pot of “mid-tones” bursting with vividness. Living with Urushi, I consider vermillion and black as the opposite extreme hues. In this piece, I composed a gradation of hues between vermillion and black.

In addition to color, Urushi possesses various textures ranging from rough to wet and slick. Furthermore, the gloss has its variations too. The intense glow from the particles of cinnabar, and the flashy glare of polished hard Urushi. The black of Urushi also becomes more profound with each additional rubbing and polishing in of raw Urushi which is naturally a translucent brown color. This mystical transformation of black into a more vibrant black, a darker darkness, cannot be made into words. It is only apprehendable by seeing in person. Sometimes, this black is called Kuro (玄: a homonym of 黒;the noun/adjective for black color. 玄 implies a deeper concept of mysterious elegance in addition to being an noun/adjective for black color). I wish to convey the fascinating colors and texture of Urushi with this piece.

Size: φ250mm×H235mm

2018 Prize at Tableware Festival 2018

2019 Chairman’s Award at 50th Kyo-sikki Exibition

2019 Prize at Craft NEXT2019

-

Button

Stacking the twelve plates for either storage or display clearly reveals the gradation of color of the composite work

-

Female-Embracing Organ – Bed / Bath for Baby

ButtonAs Urushi forms a sexy and attractive coating, I let it freely form itself in this piece. This vessel images an organic, almost membraneous embrace within.

2009 Gold prize at The Ishikawa International Urushi Exhibition 2009

Technique: Kanshitsu (dry lacquer), Shu-urushinuri (vermillion lacquer)

size: H270㎜×W640mm×D430㎜

Japanese Urushi lacquer, hemp cloth, tonoko, jinoko vermillion

-

Button

A vermillion urushi infant bathtub on a dry lacquer base, created by sculpting numerous layers of urushi-soaked hemp.

-

the capsule

ButtonCollaboration work with Yuki Kajikawa/Curator of Kahitsukan-Kyoto Museum of Contemporary Art, Director of the edit

‘the capsule began as a message capsule created by lacquer artist Yohko Toda. Upon seeing her work for the first time, I imagined her piece sheltering my last convictions as I leave this world behind. This evolved into the idea of designing a vessel for “unfulfilled communication.” I wanted to create a mystical mailbox that could deliver thoughts beyond space and time to people out of reach or even to the departed. I had many discussions with Yohko for over a year. We explored the possibilities and limitations of handcrafted metal materials and the struggles between technology and design. We were very particular about the shape not being a tube and its ability to seal properly. the capsule (2022) is the result of our collaboration, a piece that may unfold into something new in the future.’ Yuki

'With the direction of Yuki Kajikawa, the message capsule underwent a happy transformation. First of all, the capsule, which had been lying down, stood up. Similar to the flame of a candle, the smoke of an incense stick or a prayer on its way to the heavens. Rather than having a practical use, Yuki’s wish was for the message capsule to hold a letter conveying her feelings I usually use tin as a material combined with a thick layer of “urushi”. Tin is soft in texture yet sturdy. The combination of metal and lacquer was used for armors and other items throughout history, as lacquer prevents metal corrosion. This time, vermillion lacquer was applied on both the inside and the outside of the capsule. The outer veneer acts as a shield while the inner layer protects the feelings. Even if the tin tarnishes over time, it remains vermilion. I believe the capsule can preserve feelings connected by the red thread, transcending time and space. ’ Yohko

-

Button

The top of the Capsule has been removed (on right) revealing a handwritten note inside, meant to be a message to someone far away, either living or deceased.

-

figure

ButtonBlack urushi is shown dripping down a white surface, revealing its luxurious natural luster and deepth.

Film of flowing Urushi(Japanese lacquer from Natural Urushi tree), straightforward. I think Urushi is most beautiful before it’s been applied, when it’s still in its liquid form. When it’s a viscous chaotic mass of energy and nutrients. The process of creating a Urushi piece involves single-mindedly creating a perfectly smooth surface, and as I work daily facing the Urushi, I think that the smoothest a surface can be is the surface of the Urushi itself, with its smooth layer of surface tension. With the beauty of Urushi’s constantly shifting dynamic appearance, I would like for people around the world to know of this art.

video&shooting:Takeshi Asano

music:Takamasa Aoki

cooperation:TutumiAsakichi-Urushiten

-

Button

A short bristled hake brush shown applying urushi.

-

the bag

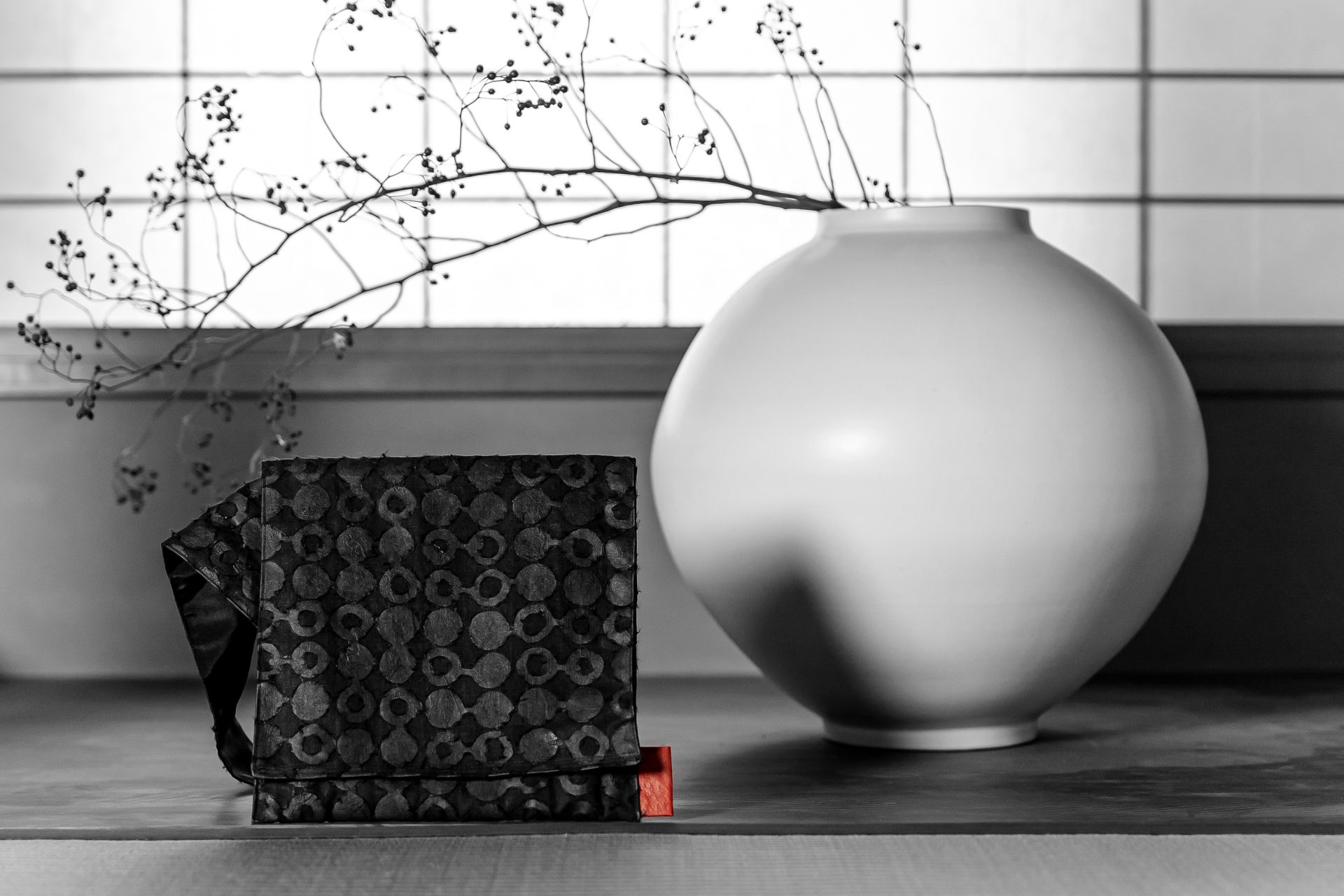

ButtonA black bag made from an original fabric by Nuno Textiles, and featuring a red urushi-coated tag.

-

The bag

ButtonA black bag made from an original fabric by Nuno Textiles, and featuring a red urushi-coated tag.

"The bag was a gift from my dear friend and photographer Sarah Moon. I fell in love with the bag at first sight, and have taken it everywhere for many years.

Sarah's friendship with the bag’s creator when she was a model in the 1960s and their bonding story inspired me to launch my own brand and create bags in Kyoto.

While exploring materials, colors and proportions to realize my vision, I met with unexpected coincidences, such as the creation of the red urushi lacquer-coated silk tag. The bag is like a record of a my journey of friendship."

CONTACT ・ Yohko TODA + the edit

Website (English): Urushi Media / the edit

Instagram: @yokunettete / @theeditkyoto

Japancraft21: Email Us