Click Image to Enlarge

Write whatever you want about this artwork.

This white kimono begins with an extremely thin undyed white silk woven in a very subtle pattern. The silk is then dyed a more subtle shade of white. An outline is then drawn of the banana leaf motif with a fine brush and a water-based dye. The outline is then traced over using a resist paste, making a 3-dimensional line around each leaf. The outlined leaves are then filled in with oyster shell white dye, which is followed by the addition of darker white to create appropriate shading. The silk is presented in two layers, so we see the banana leaf motif on both the surface silk and on the second layer, creating a sense of depth.

Asako TAKEMI

Textile Dyeing・Kyoto

-

Artist's Story

Asako TAKEMI is a textile producer who is bringing contemporary design to Japan’s legendary hand dyeing and weaving arts. She is dedicated to preserving the best dyeing techniques in the Kyoto kimono industry, single-handedly saving the lifelong skills of 10 venerated elderly Kyoto dyers. With Takemi’s deep and soulful love of fabrics and strong design background, she creates original kimono and Western-style ensembles for her clients, whose personal tastes influence the designs.

Currently she is spearheading JapanCraft21’s hand-dyeing apprentice program. It is her vision to rescue and revitalize these centuries-old dye techniques, clarifying and reassessing dye culture to meet current needs in an ever-shifting apparel market.

By choosing already experienced mid-level dyers as apprentices for intensive training by master dyers, bringing them up to master level takes about two to three years’ time rather than the decade it would take to train beginners. JapanCraft21 provides cost-of-living stipends to the apprentices so they can concentrate full time on their training.

-

About the Craft

Silk Dyeing. Silk is said to be the strongest natural textile in the world. Silk production (sericulture) was introduced to Japan from China around the 4th century. Of the four main silk types (Tussah silk, Muga silk, Spider silk, and Mulberry silk), Mulberry silk (silkworms fed on mulberry leaves) is mostly used in Japan as it creates the softest fabric.

Asako TAKEMI is working with ten of Kyoto’s most skilled silk dyers (aged from 70 to mid-90s) to save legendary dye processes from extinction through an accelerated apprentice program that she created with JC21. Combining these ten specialty techniques results in an almost endless number of variations. For example, stencil-dyed patterns can be combined with hand-brushed gradation dyeing. Or suminagashi (floating ink, marbling) can be combined with brush-dying resulting in an endless range of color combinations.

The Craft of Silk Dyeing

Silk threads are shaped like translucent glass rods with a slightly round triangular cross-section and prismatic structure, so they transmit and reflect light through their structure and emit a complex diamond-like brilliance.

Various dyeing techniques fall into two broad categories: (1) yarn is dyed first and then woven (sakizome), and (2) undyed yarn is woven with the dye applied to the finished woven silk (atozome).

- Sakizome Types: Patterned weaves, pongee (tsumugi), and ikat (kassuri) patterns

- Atozome Types: Yuzen (hand-dyed with small brushes), stencil dyeing (including komon or small pattern dyeing), and shibori (tie-dyeing)

Atozome Dyeing Techniques

- Stencil dyeing (including komon) involves minute and complex designs. The silk is laid out on a long table. Narrow stencils are reused many times during the dyeing process. A resist paste is then applied to the stencil and the piece is dyed by hand with brushes. The resist paste is then removed to reveal the undyed silk or dye color applied before the application of the stencil dye. Oftentimes, the undyed portions will then be yuzen brush-dyed, following the stencil-dye process.

- Yuzen dyeing utilizes tiny brushes. This could be compared to painting on a canvas using dyes instead of paints. The yuzen technique is used to produce amazing subtleties of color gradation, for which Japanese dyers are renowned.

- Resist dyeing is a traditional method of dyeing textiles using dye patterns or tie dyeing. For pattern dyeing, a thick paste (made from rice starch, seaweed, or a modern manufactured material) resist agent is applied to the fabric to prevent the dye from reaching all the cloth. Wax is often used for non-stencil, freehand dyeing.

- Suminagashi (floating ink, marbling) uses black sumi ink and a dispersant (non-ionic surfactant that helps to keep the dye in a dispersed form), that is floated on the surface of the water creating a marbled effect.

- Kinsai dyeing is the application of metal leaf to the surface of the fabric creating decorative accents.

- Textured removal of dye through absorption. After the dye is applied to the silk, a sawdust-like substance is piled on the still-wet-with-dye silk. The sawdust substance absorbs some of the dye from the silk resulting in a textured effect.

- Color application and color removal in patterns. Dye is applied to the fabric with a stencil, then another stencil is placed above the dyed section and a bleaching agent is applied to remove some of the color. This application and removal process is repeated several times to achieve a blurred effect.

- Combination stencil and shibori tie-dye with the application of kinsai metal leaf.

- Combination stencil dye and gradation dye.

- Undyed white silk is dyed a more brilliant white color.

Yuzen Dyeing

Utilizing tiny brushes, this technique could be compared to painting on a canvas using dyes instead of paints. Even large expanses of solid color are masterfully applied with small brushes resulting in blotch-free color which is as even and consistent as dip dyed fabric. For this, the tanmono (a variable measure for fabric) is stretched for its entire 12-meter length by tying the two sides of a long narrow room. The 35-40 cm width of the silk is stretched (selvage-edge to selvage-edge) with thin, Japanese shinshi needle-tipped bamboo sticks.

Primary Steps in Yuzen Dyeing

- An outline of the design is drawn on paper.

- The paper drawing is placed on a glass table and plain, undyed silk tan fabric is placed over it. A light is shone from under the glass so the design from the paper can be easily seen through the silk allowing for tracing, which is done with a water-soluble dye using a fine brush.

- The painted outline design on the silk is next covered by a fine brush with a resist paste.

- The design, defined by the outlines, is then filled in by fine brushes with colored dye, often applying color gradation.

- The resist substance is then removed.

-

Click Image to Enlarge

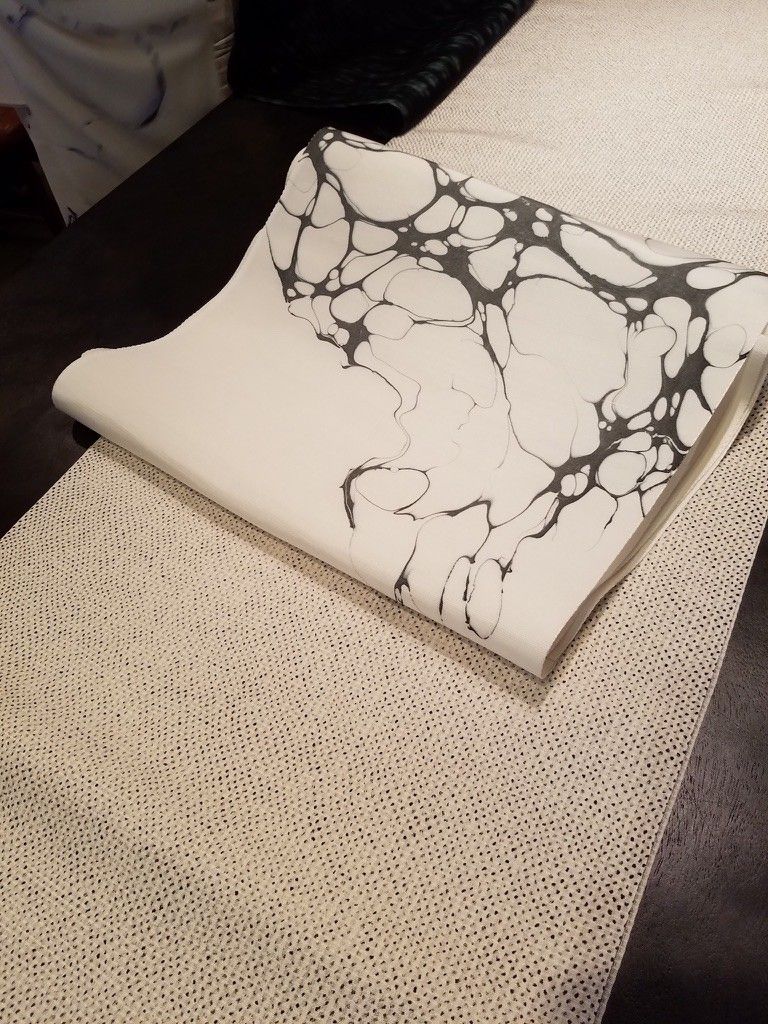

ButtonThe color of the natural white silk was further enhanced with a rich white dye. The white fabric is slightly dipped onto the surface of water upon which floats black sumi ink (made from pine soot and a natural binder) in suspension to achieve this original marbling effect introduced by Takemi.

-

Click Image to Enlarge

ButtonThe silk is dyed beige with small brush along its entire 14-meter (43-foot) length. Stripe application: a. resist paste is spread repeatedly 35 times with spatula-like tool along full length of silk; b. exposed stripes dyed with darker color with small brushes in a purposely random gradation of color; c. paste is removed to expose beige.

-

Click Image to Enlarge

Buttona banana leaf motif is dyed with tiny brushes and oyster shell dye onto a very sheer piece of white silk.

-

Click Image to Enlarge

Buttona banana leaf motif is dyed with tiny brushes and oyster shell dye onto two superimposed layers of very sheer white silk.

-

Click Image to Enlarge

ButtonThe color of the natural white silk was further enhanced with a rich white dye. The white fabric is slightly dipped onto the surface of water upon which floats black sumi ink (made from pine soot and a natural binder) in suspension to achieve this original marbling effect introduced by Takemi.

-

Click to Enlarge Image

ButtonThe obi sash is a complex piece that begins with stencil-resist dyeing and applying color to exposed parts with small brushes, removing the resist paste by steaming, then folding the piece in tsutsuzome style tie-dye shibori, applying dye to the exposed areas, spreading the piece open then applying mica by hand.

-

Click to Enlarge Image

ButtonThis piece is stencil dyed in a slightly irregular pattern, which gives an energic feel.

-

Click Image to Enlarge

ButtonResist paste spread repeatedly with small hand-cut stencil, 30cm at a time about 35 times along a 13 meter (43 foot) piece of silk. The silk is then dyed with small brushes, paste is removed, white places are exposed wherever the resist was applied. Further dying with small brushes of the white places may follow.

-

Button

This is a yuzen-dyed piece. Yuzen brush dyeing uses flat brushes and achieves exceptional consistency of color without streaking. A dye-resist paste is used for the two-tone effect.

-

Button

Though appearing to be a woven pattern, the design was achieved by stencil dyeing.

-

Button

The process begins with dyeing tiny dots in stripes by applying a paste containing black dye over a stencil. Then a warm beige colored dye is applied yuzen-style from end to end with a flat brush.

Unlike the identically sized and placed dots from a machine-cut stencil, a hand-cut stencil with intentional variations in dot size and placement results in a subtle sense of energy and vitality.